Jumping into Java

Welcome to CS 201!

This class assumes that you have previously taken CS 111 and know Python. If you are one of the folks that are coming from high school AP, you will have to bear with me when I assume that you know Python and are learning Java. (Also, you should make a plan for learning Python if you are going to take more CS classes, since many assume you know Python.) One of the big changes from CS 111 to CS 201 is switching from Python to Java and I know that it will be a bit uncomfortable at first, but I promise that it will get easier.

Why Java?

I know, I know. You just got comfortable(ish) with Python and now you’re being asked to switch and you want to know why. There are several reasons that we (the CS faculty) think that it’s important for you to learn a new programming language:

- It helps you learn about general principles of programming that are separate from any one language.

- It’s important to learn how to learn new programming languages quickly; the language that you’ll be using in 10 years may not even exist currently!

- Different languages are better at different things: Python is good for beginners, Java can be faster and more reliable. As a compiled language, Java offers some advantages, including that the compiler detects errors before they happen and the compiler can optimize our code (compile once, run many times).

- One of our goals of this course is to learn about object-oriented programming, and Java pretty much forces you to do object-oriented programming.

- Java has some key differences that are important for you to understand, like static-typing and compilation.

- Java is still among top 3 most-used programming languages (with JavaScript, Python, C)

Major Differences

You’ve already seen some Java and have been able to compare it to Python, so you probably have some ideas of visual differences. Here, I’ll put labels onto some of the things you’ve already seen and some explanation for things happening underneath.

Under the Hood

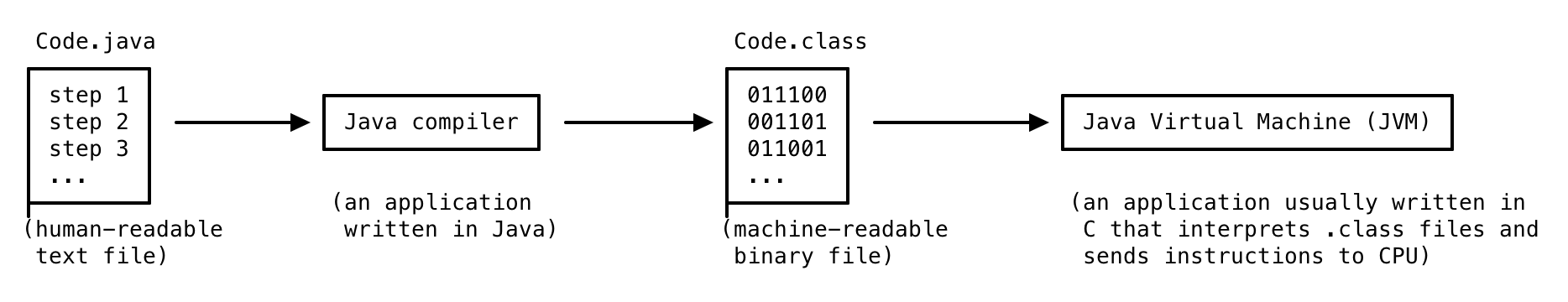

Java, unlike Python, is a compiled language. This means the code must go through a translation (i.e., must be compiled) before it can be run. A sketch of this process is shown below:

-

Code.javais a text file containing the human-readable version of the code, just like a.pyfile -

The Java compiler translates the

.javafile into a binary.classfile (binary meaning it contains data in raw 1s and 0s that can’t directly be interpreted as text). This format is also referred to as Java bytecode. -

To run the compiled program, the

.classfile is given as input to the Java Virtual Machine, which interprets the Java bytecode and sends the corresponding instructions to the CPU

Caveats

No programming language is perfect, and Java certainly has some weaknesses. There are going to be a lot of rules but also exceptions to those rules and things that don’t follow the overall pattern. There are a variety of reasons for this, including:

- The language has evolved over time since the 1990s

- Adding some complexity allows programmers to achieve better performance

- There were some bad early decisions that must be kept to maintain compatibility

Variables

In Java, variables have to be declared with a type before you can use them. In Python, you could just put whatever data you wanted into a variable, but Java is picky about you sticking to what kind of data you said you were going to use.

There are primitive and reference types.

Primitive Types

The six primitive types are (notice that their names all start with lowercase):

| Name | Type | Range | Default Value |

|---|---|---|---|

boolean |

Boolean | true or false | false |

char |

Character data | Any character | ‘\0’ (zero) |

int |

Integer | −231…231−1 | 0 |

long |

Long integer | −263…263−1 | 0 |

float |

Real | −3.4028e38…3.4028e38 | 0.0 |

double |

Double precision real | −1.7977e308…1.7977e308 | 0.0 |

If you want to change from one type to another, you can, but you have to tell Java to do it purposefully with a type cast:

double my_double = 1.5;

int my_int = (int)my_double; //cuts off the .5

Caveats

You can do most of the normal things with the primitive types such as addition and subtraction, etc.

You also use == and != on the primitive types.

In fact, you should ONLY use == and != on the primitive types; if you use it with anything not on the above list, it will not do what you expect!

You will almost certainly forget this and run into a weird bug where strings don’t do what you expect, so try to remember this when strings are being weird :).

Also, unlike Python, / will perform integer division if both operands are integers (i.e., the decimal part of the result will be discarded).

Finally, char is actually an integer type, holding the integer value corresponding to the given character under the Unicode-16 standard, so you can add them together.

What about Strings?

You might have noticed strings were not among the primitive types, only individual characters. This is because strings are represented as objects in Java, which are fundamentally different from the primitive types. Some key differences:

- Object type names are capitalized (String)

- Primitive variables store the value, but object variables are references (and hence also called reference types)

- References store the memory address of the object (kind of like telling your friend your home address instead of giving them an entire copy of your house)

- See the official API documentation if you want to know everything there is to know about Strings.

Objects and Classes

As you noticed in the lab, there is a lot of boilerplate code that you need for even the most basic task in Java.

That’s because everything, and I mean everything, in Java has to be in a class, including your main.

If you run a Java file, it will run whatever is in main (or yell at you if there is no main).

We’ll talk more about all the things going on in that boilerplate Soon(TM)

Because everything in Java is in a class, every function or method that you use will have to be a class method and every variable will belong to an object or its class.

You saw this when you saw how to read from a file: you had to deal with the File, Scanner, and System classes because you used all of their methods.

Let’s look at a new example quick:

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

This is how you get input from the user once a program is running (add this to your reference sheet!).

In this line, you are declaring and instantiating a new Scanner object and passing it the object System.in, which always already exists because it is the input from the computer’s keyboard.

Arrays

Arrays in Java are objects (like Strings), but have several special properties/quirks.

Also, keep in mind that “arrays” are different than “Lists”, which are a little bit different from “ArrayLists”.

Unlike all other data structures in Java, array length is a field, not a method.

For example, you would do args.length to get the length of an array called args, but you would do s.length() to get the length of a String s.

An array type (i.e. what you are putting into the array) is given by adding square brackets to the type of data in the array (e.g., String[] for an array of Strings).

Arrays are fixed length and can only contain a single type of data.

You can’t mix numbers and strings in a single array (unlike Python lists).

You can change array elements, but you can’t add or remove them (unlike Python lists).

Arrays are the only thing in Java that can be indexed with square brackets.

They are zero-indexed.

java.util.Arrays provides a lot of useful array-related functions.

JavaDocs

Throughout the course you’ll be required to include informative comments above each method in “JavaDocs” style. This style allows for a website to be generated with those comments nicely formatted and looking like the Java documentation that you’ll become quite familiar with.

JavaDocs style is the following:

/**

* Generally descriptive few sentences about the method.

* @param nameOfParameter description of the parameter if useful, probably should mention the type

* @param anotherParameter if you have multiple parameters

* @return description of what if anything is returned, should definitely mention the type

*/

public int exampleMethod(int nameOfParameter, int anotherParameter){

return 0;

}

Making the Jump

A common problem that I see with students at the start of Data Structures is that they think they should jump write into fluently writing Java programs. It will take time to get comfortable with Java and that’s okay! My main recommendation when you are starting out is to separate the two hard things that you are trying to do:

- Figure out what you want your code to do

- Figure out how to do that in Java

You can do the first thing in pseudo-code or even in Python. Once you’ve decided what you want the program to do, you can then use your reference sheet to figure out how to do each piece in Java.

Acknowledgements

Sections of this page are directly from Prof. Aaron Bauer and used with permission. Thanks Aaron!